A Creek Called Mary by Bill Barlee

[Admin Note: With what appears to be the onset of a possibly early spring in the Cariboo Gold Fields I thought that all the placer miners would enjoy a bit of inspiring reading to get the old gold fever running through our veins again and maybe motivate everyone to get busy on their Notices of Work early enough so that when the creeks are running and the gravels are exposed we can get off to an early and productive year of mining. Enjoy!]

From Vol. 5, No. 4 of Canada West magazine, Fall 1974

From Vol. 5, No. 4 of Canada West magazine, Fall 1974

There is only a handful of names; “Big Alex” McDonald, “Cariboo” Cameron, Charley “The Lucky Swede” Anderson, Billy Barker, Clarence Berry, “Swiftwater Bill” Gates and perhaps a few others, but probably no more than twenty in all. It’s a unique group because these men were among the few who struck it rich on the gold creeks of the Klondike and the Cariboo – they were the legendary placer kings of the old west.

One more name could be added to the list, one you’ve probably never heard of before – Terry Toop – an unusual name for an unusual man, one of the last of a vanishing fraternity, an old-time prospector.

It has often been stated that all of the great placer gold discoveries have already been made and, generally, this assumption is true. The Klondike, Cariboo, Atlin, Cassiar and other celebrated goldfields were all found in a forty year span from 1857 to 1898. In those four decades, creeks with names like Eldorado, Bonanza, Hunker, Williams, Lightning, Spruce and Pine became almost household words, and men from all walks of life dreamt of striking gold in the far west. That era passed when, inevitably, the once plentiful supply of gold from the placer creeks dwindled to a fraction of the production of the bonanza days.

In the years which followed, only hard times, such as the depression of the 1930s, brought renewed interest in placer mining. A few new creeks like Squaw, Wheaton and Harris were discovered then, but these finds were the rare exceptions and when the depression finally ended, placer mining, as a way of life, had almost ceased.

By the early 1960s there were only about three dozen serious placer miners at work in British Columbia, although there were quite a few more still operating in the Yukon. Along scattered creeks in various parts of the interior, occasional miners could be found, some of them reworking old tailings, others seeking new ground or ancient channels. These were the die-hards, the convinced placer men who believed that there was still a future in placer mining. One of these was a man named Terry Toop, a man who had followed a strange hunch for most of his long years in mining.

The Toop family had long roots in British Columbia; several branches of the family arrived in the province in the early 1860s and their descendants had never left, remaining to farm in the Chilliwack area of the Fraser Valley. Terry had been brought up in Chilliwack and had early become fascinated with placer mining when a favourite uncle, Art Youngen, an old placer miner, entertained his nephews through the winter nights with stories about rich placer creeks and the prospectors who found them. By the time Terry reached twelve he had decided; someday he would become a placer miner. In 1934, at the age of 17, and in the depths of the depression, he realized his ambition when he set out on his first prospecting expedition. It was into the Horsefly Country and lasted nearly eight months. Although the trip did not prove profitable, it did provide him with a taste of a life which he had only imagined previously. From that day on Terry Toop seldom strayed from the placer miner’s way of life and he never forgot his boyhood dream “to find placer ground where nuggets were visible in the gravel.”

The years that followed took him into nearly every corner of the province; from the Chilcotin to the Bridge River, from Likely back to Horsefly, up to the Yukon and into a dozen other regions, always searching for his Eldorado. The prospects were sometimes promising, but none of them ever panned out. By the 1950s Terry had a wife and a growing family to support, and at this critical period a series of strange coincidences occurred. The first was his decision to follow an impulse, almost a blind hunch that he should prospect the Cottonwood country, north of historic Cottonwood House. Although this region was in the Cariboo between Quesnel and Barkerville it had never been considered good placer ground and had generally been ignored by many knowledgeable prospectors. Nevertheless, acting on his long held belief, Terry obtained a trapline in the area. Trapping in the winter to remain solvent, he prospected in the spring, summer and fall.

Following this routine each year he combed the country north of Cottonwood House and finally decided on an old gold creek called Umiti, a tributary of the Cottonwood River. It was a stream which had yielded interesting amounts of gold since the 1860s and when he struck a likely looking prospect near the headwaters of the creek it seemed to vindicate his theory that this was the creek for which he had long been searching. After several years of prospecting on it, however, it too proved disappointing, the lead was poorly defined and generally spotty. Umiti was not the creek.

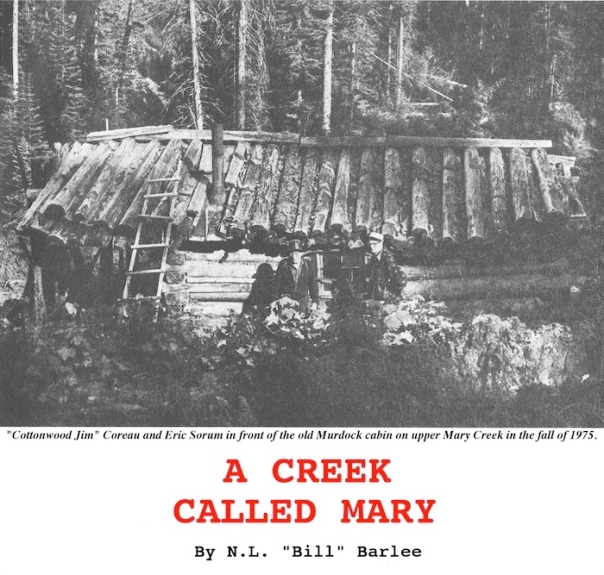

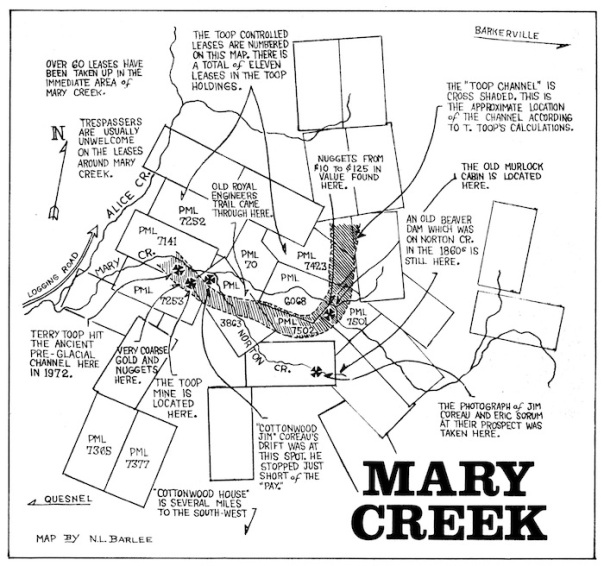

By then it was 1968 and Terry Toop had been prospecting for thirty-four years, and although he was an experienced and knowledgeable prospector, he had little else to show for his decades of searching. His wife Marge, fortunately, was just as resolute as her husband and, in the spring of 1969, still convinced that his bonanza creek lay somewhere north of Cottonwood House, Terry shifted his area of operations. Still guided by his hunch, he decided to prospect a creek called Mary, a small tributary of John Boyd Creek which eventually flowed into the Cottonwood River. Initially, the stream didn’t appear to be very promising. Although it had been found to be gold bearing in the early 1860s, it had been mined only sporadically since, and had never been a noted producer. The mining records were equally discouraging and contained only brief reference the “Old San Juan” placer mine which had once been located just above the junction of Mary and a tributary, Norton Creek. Despite its bleak record, two prospectors were still mining in the area, “Cottonwood Jim” Coreau, on Norton, and Eric Sorum, on Mary. Both were old miners and had been in the region since the early 1930s. Intrigued by the coarse gold they occasionally recovered, they had been mining their leases of and on for years.

After examining the ground, and then looking at the maps of the region, Toop noticed several peculiarities; one section of Mary, above the junction, had been unusually rich and had produced coarse gold and nuggets, whereas the remainder of the stream had been generally barren. The same applied to Norton where only a fraction of the creek had been exceptionally productive.

Perplexed, Toop meditated over this. Perusing the map again he noticed that although the good paying sections were on different creeks they weren’t really that far apart. Then the realization came to him – both pay sections could have been parts of an ancient channel which had once cut across the streams leaving two separate pay areas.

It was a long-shot theory, but one which was just logical enough to check out. In the weeks that followed, Terry Toop carefully investigated all of the geological features of the region and discovered that there were high rims on either side of the draw through which the creeks flowed. These rims, he figured, would have provided protection from glaciation for an ancient channel, if one actually did exist.

Now he had to determine whether or not there was an old channel. He had noticed glacial till and other signs of glaciation in the general area, but not in the protected draw. It was a sign which tended to support his premise. So much, in fact, that he was convinced that he was on the right track.

In the spring of 1969, he decided to stake on Mary Creek. His lease started on Mary and ran upstream almost to the point where its tributary creek, Norton, joined it. It was a section of the creek which had been neglected for decades. With his son Gary, Terry Toop probed the gravels along Mary Creek, hoping to find a clue which would lead to an undiscovered paystreak. Patiently testing the ground near the stream they found only fine “flour” gold, a disappointing sign, and one which was certainly not indicative of the ancient channel for which they had been searching. Finally, after months of exhausting work failed to turn up anything even remotely resembling an old “lost” channel, the Toops reluctantly abandoned their strange quest.

So Terry Toop walked away from Mary Creek, disheartened that it, like Umiti, and so many other half-forgotten placer streams before it, had failed to live up to the first high expectations. For the remainder of that year and on through 1970, the Toop lease on Mary Creek lay undisturbed and yet, Terry Toop, despite his failure to find any trace of a supposed old channel, could not get the creek out of his mind. For months his thoughts kept slipping back to the region. Over and over again he reviewed the clues; two rich pay sections on two different streams with little worthwhile ground beyond those two areas, and gold so similar that it must have originated from the same source. There could be one answer only – there had to be an ancient channel somewhere in the area.

Finally, in the spring of 1971, restless and unable to shake his theory out of his mind, Terry Toop almost reluctantly returned to Mary Creek. Having neglected to file his assessment work in 1969, his placer lease had reverted back to the Crown. Back on the stream he noted, almost sardonically, that no-one else had even bothered to pick up his old lease. Once again, in the name of his son Gary, he claimed the ground.

This time, he determined, he would find out, once and for all, whether or not there was a lost channel. With his son, he again began to prospect along the creek. Day after day they toiled in the draw, searching for any signs or clues which would prove their “lost channel” theory. Summer and fall passed, and at the end of the year they realized that they were no further ahead than they had been when they started two years before. It appeared that their lease on Mary Creek was completely barren.

At that point abandonment of the creek seemed justified but something, a certain unexplainable feeling, compelled him to hang on. Terry knew his great-grandfather, William Matthew Hall, once a Royal Engineer, had camped at the junction of Mary and Norton creeks in the early 1860s when the Royal Engineers were building a trail through to Barkerville. Although that route had been abandoned in 1864, Toop found it an eerie coincidence that his great-grandfather, a hundred years before, had camped just yards away from his lease. There were just too many oddities about the stream and always, at the back of his mind, was the persistent feeling that this was the creek which he had been looking for.

Sometimes a prospector follows his hunches, it’s not usually the best way to prospect, but occasionally, when the hunch is strong enough, the miner stays with it. So it was with Terry Toop and in the spring of 1972 they were back on their Mary Creek lease once again. The old routine continued, the back-breaking labour of working to bedrock and the results were the same, each time they came up empty-handed. By the fall of that season, the Toops had carefully prospected nearly all of their lease and had been completely baffled in their attempts to find the hypothetical old channel. Despondent, Terry Toop had decided that this would be their final effort on the creek, there was, after all, a difference between persistence and bull-headedness and maybe, he felt, after three years of frustration on the creek he had passed from that first stage into the second.

It was October, and with winter imminent there was only time, at the most, for several more weeks of prospecting. Terry, for the hundredth time, went over the particulars of the region. He had, he was convinced, prospected every possible place in the draw. Where, he puzzled, could an ancient channel be? Idly his critical eyes surveyed the creek. The banks were fairly steep, generally a rather poor indicator for an old channel. He and Gary had tested bedrock in a number of places along the creek bottom and on the north side of the stream. The only place they hadn’t checked thoroughly was the south bank, and the reason was obvious, it simply didn’t look geologically encouraging enough.

But time was a factor and an increasingly more important one as winter loomed closer. Shrugging, Terry told his son and old Eric Sorum, who had joined them for the day, that maybe they should try the south bank again. So the three prospectors, armed with picks, shovels and gold pans, waded the creek and climbed up the slopes of the south bank. This time, Terry figured, he would test the gravel a little higher up than he had previously. As he studied the ground his gaze came to rest on a slide about twenty feet above the creek.

“Just below that silde is about as good a place as any,” he said as he pointed up the bank to the spot.

They reached the designated place and as Terry cleaned off the surface debris he noticed ashes and burnt wood. Evidently someone, long ago, had built a campfire on the spot. Within half an hour he had managed to reach a depth of nearly three feet. As he dug down into the gravel he noticed that its colour was changing. Just past the three foot level a grey-blue layer became predominant. Toop examined it closely. Was this the historic and celebrated “blue lead” of the Cariboo? At three and a half feet, and still in the blue clay, he stopped and reached for a gold pan. Silently he filled the pan with gravel and clay and then passed it to Eric Sorum. A moment later he heard the old Scandinavian gasp. Glancing up Terry saw the old prospector peering intently into the pan.

“A nugget!” he whispered hoarsely. And reaching into the pan he pulled out a glittering piece of gold.

Both Toops stared wide-eyed at it. It had to be close to twenty dollars in size! Several thoughts quickly passed through Terry’s mind. Was it a fluke or had they actually hit the ancient channel for which they had been searching? He turned his attention back to excavation. Almost immediately a glint caught his eye. Reaching down he pried at the object. It dropped heavily into his outstretched hand. Slowly, between two fingers, he turned it over and then held it up for examination.

The unmistakeable lustre of nugget gold greeted his companions.

“A thirty dollar slug!” he said finally.

“That was the moment,” Terry later related, “that I knew my dream had come true – the nugget had actually fallen right out of the gravel, just as I had dreamt.”

Within minutes the scene had been transformed, the very air seemed charged with energy as the three prospectors dug feverishly into the blue gravel. After an hour had passed they knew that they were on the old channel. By the time the sun went down that afternoon they had amassed hundreds of dollars in nugget gold; enough to convince them that they had hit a bonanza.

That night, when the two Toops returned to their home south of Quesnel, they were in rare high spirits. Terry’s wife, Marge, later recalled that it was like trying to talk to “two crazy men” when they first arrived and attempted to tell her about their strike. Eventually they managed to convince her that they had finally “hit it,” and that their long search was over. In the days that followed that claim was borne out.

For the few remaining weeks of the fall the Toops worked their lease on Mary Creek and recovered quantities of coarse gold. Careful testing, however, indicated that that the pay might not extend beyond two hundred yards, a sobering thought. But the ground was so rich that even that relatively short stretch would undoubtedly yield many thousands of dollars in placer gold. When winter eventually closed down their operations, the Toops, for the first time since their discovery, relaxed and began to make plans for the spring of 1973.

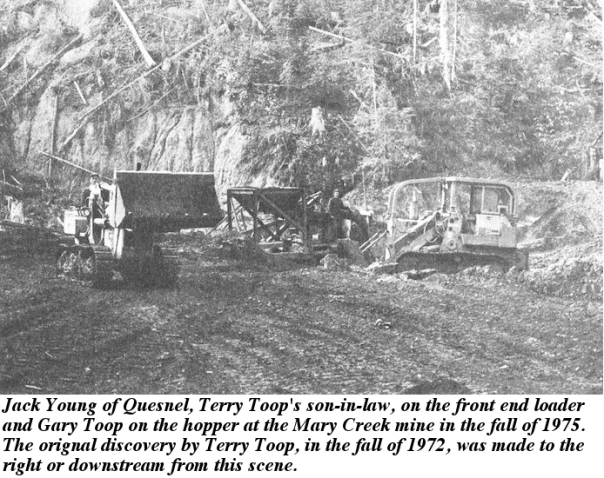

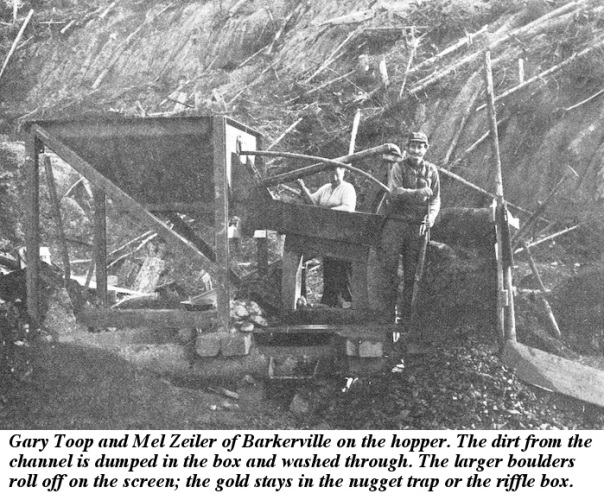

It was early spring when the Toops went back to Mary Creek. During the winter layoff they had built a hopper, complete with a grizzly and riffle box, and had managed to obtain a small front-end loader – items which would enable them to mine on a much larger scale than they had before.

Moving into a new cabin near the creek, they settled in and began working the bench. They weren’t disappointed. Almost immediately they accumulated impressive amounts of coarse gold and nuggets. Surprisingly, very little fine gold was found. It augured well for the future.

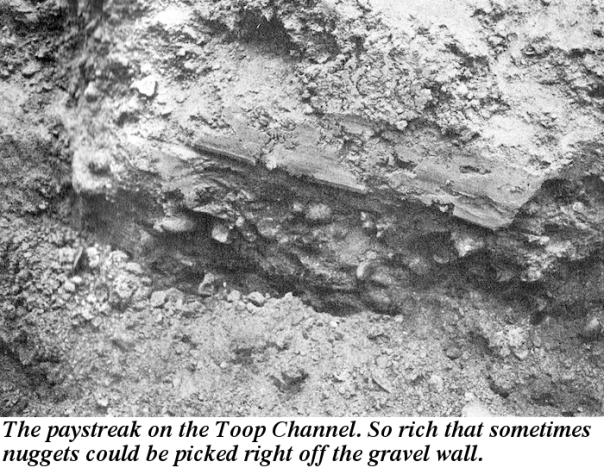

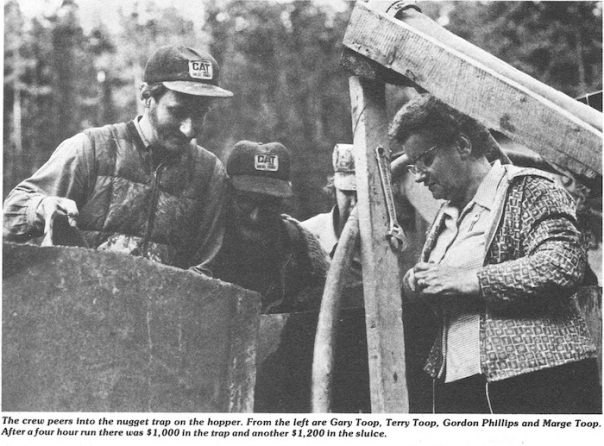

Day by day, week after week, the claim continued to yield. A yield so spectacular that it was reckoned in pounds, not ounces, as was the usual practice. One memorable evening, after supper, Marge and Terry Toop walked down to the claim and picked up, with their fingers, over $2,200 in nuggets – and all of it from a single yard of gravel. In fact, it was not unusual for any of them to pick nuggets right out of the gravel wall when they were mining. The gold, which was copper coloured and often oxidized, had nuggets ranging up to $150 value. Many of the pieces, as an added bonus, were exquisite jewelry specimens. As the spring wore on the total yield climbed steadily. Then, one unforgettable morning, an event which every miner fears, occurred. The pay abruptly came to an end.

Alarmed, the Toops prospected in every direction in an attempt to relocate the run, but to no avail, the pay had simply stopped. Puzzled, Terry Toop examined the ground. His experienced eyes perceived that the boulder clay was tight on bedrock, a discouraging sign. Every indication signified an end to the paystreak. Most miners would have accepted the apparent termination of the pay, for all runs of placer gold, sooner or later, come to an end, but Terry Toop, still gripped by his obsession, balked at abandoning his lease again.

With tenacious determination, they tested the ground again, and once more came up empty-handed. Finally, after every other possible avenue had been exhausted, Terry decided to try to break through a wall of bedrock which faced upstream in the hopes that the bedrock, if it was only a few feet thick, had cut off the pay only temporarily, and that once through it he would strike the run again. It was a slim chance and one which didn’t appear reassuring, but with no other alternative he drove into the wall. It was tough going – one foot, then two, three, five. With mounting despair they doggedly continued. Six, seven then eight, then suddenly the bedrock dropped away and a channel with the familiar blue boulder clay lay exposed. Was it the continuation of the rich channel or would it be barren? The Toops and Mel Zeiler, a prospector and friend from Barkerville, anxiously filled their gold pans and scrambled down to Mary Creek to pan out their dirt.

A few minutes later they had their answer – tell-tale pieces of gold lay glittering in every pan. They were elated, they had hit the ancient channel again! For the next few hours they panned continuously and with pans yielding anywhere from $9 to $22 a pan, they were convinced.

Soon after, bullion in 15 and 20 pound lots was being shipped to a refinery in Richmond, and although photographs of the nuggets had been published in the large coast newspapers, and had caused quite a stir, the origin of the gold was known only locally. Terry, however, aware that his find couldn’t be kept a secret much longer, had moved to consolidate the ground around his lease. He was just in time, for by the late summer of 1973, word was filtering out that the Toops had “hit it big on Mary Creek.” By then the Toops had staked the vacant ground around their lease.

1973 surpassed their expectations. The returns in fact were almost incredible. Marge Toop’s brother, Fenn Williams, became so proficient at sniping that he soon earned the sobriquet “Sniper.” His one man operations were so lucrative that it was considered a poor day when he didn’t recover several ounces for his troubles. And the main operations were gleaning up to two pounds per day. By the time the season ended, Terry Toop realized that the “run” continued upstream for at least a mile, and possible more. It was becoming increasingly imperative that he obtain the old leases on Mary and Norton.

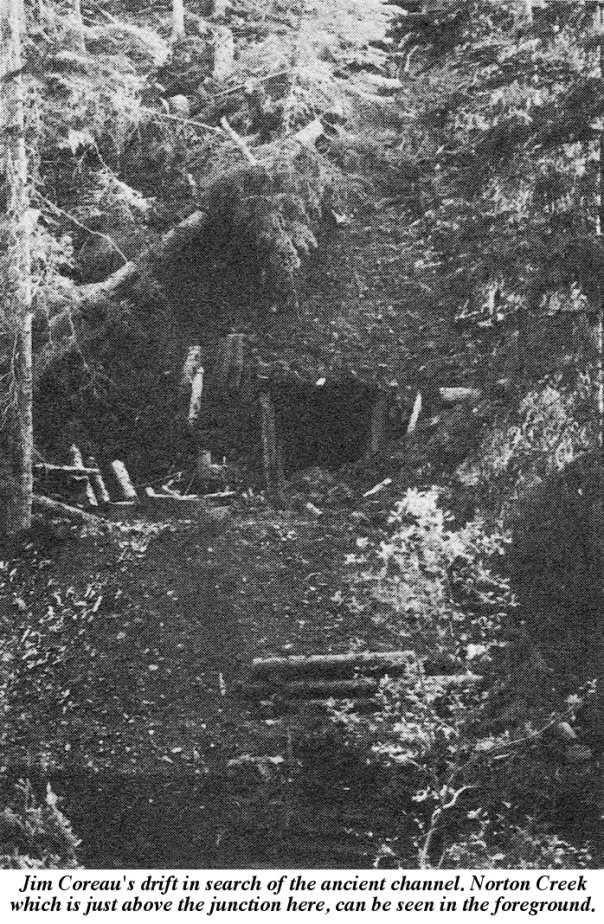

In the spring of 1974 the Toops purchased Placer Mining Lease No. 6068 from Jim Coreau. “Cottonwood Jim”, however, assuming that the old channel extended upstream, held onto his lease on lower Norton which was next to the Toop’s main lease. That summer he drifted in just above their ground, hoping to cut the old run. After thirty-two feet of backbreaking work Coreau abandoned his tunnel, unaware that his guess had been right on and that he had stopped only a few feet short of the ancient channel – just a fraction away from hundreds of thousands of dollars in placer gold. That season followed the pattern of the year before, but by now their find was a poorly kept secret and other miners, and some speculators, were moving in and staking ground all around the area. By the end of the season most of the available ground had been taken up.

In 1975 a stroke of good fortune enabled the Toops to pick up some ground they had always wanted; Eric Sorum’s lease away up on Mary Creek. The old Scandinavian had sold his property to a consortium from the coast, but they had failed to pay the assessment fee of $30 after they had taken over. Another party from Abbotsford discovered their error and re-staked the ground, but neglected to stake from the original “initial” stake, instead staking from the old “final” stake back. It was an error which they were to rue for they missed a “fraction” which was the best ground on the old lease. Terry Toop, after checking, noticed their mistake and immediately staked the leftover fraction. Soon after “Cottonwood Jim” Coreau decided to sell his main lease to the Toops. With the acquisition of Placer Mining Lease No. 3863 from Coreau, and with Sorum’s fraction, the Toops controlled more than a mile of ground, enough to keep them mining for half a century. With eleven leases on the two creeks they had locked up the best of the ground.

And 1975 was another banner year. Like the two seasons before it, the stream of placer gold flowed unendingly, as did the bullion shipments to the refinery. The mine had also expanded, from essentially a one family operation to a larger concern; when Jack and Gordon Phillips, two crane operators from Quesnel joined the group to remove the overburden after the paystreak had swung into a deep bank.

The depth of the channel had also increased, and for the first time there were two runs of gold instead of one; the first in the blue-grey boulder clay, and the second several feet lower in a cemented reddish-coloured gravel. The paystreaks, especially towards the end of the year, were incredible. In one five day span in late September a total of 127 ounces – over 10 pounds troy – was recovered. The gold value alone was close to $20,000 and probably $25,000 or more when the premium for coarse gold and nuggets was taken into account. An average of $5,000 a day!

The Toop Channel, discovered only three years ago, promises to be one of the greatest placer gold discoveries of the province in this century, and may even rank alongside the illustrious finds of the mid-1860s. The ground that William Matthew Hall walked across more than a hundred years ago promises to yield anywhere from $7,000,000 to $15,000,000 in placer gold. Only a tiny fraction of the old run has been mined, and the centre of the ancient pre-glacial channel hasn’t yet been reached. It is truly a bonanza creek.

As for Terry Toop, his long quest for a creek where the “nuggets fall free from the gravel,” is over.

——

Posted on February 16, 2013, in Golden Tales & Poems. Bookmark the permalink. 4 Comments.

Thank you sooo much for posting that, I have been searching for it forever and it is a remarkable read!

Awesome story……

great story, thanks

Hello you lucky people who have had the experience of knowing the Toop family. I myself have had the distinct pleasure of knowing all of them very well over the past 40 years or so, and at the moment, am the acting Agent for Gary Toop and Ethel Toop, Gary’s step mother. This family just happened to change the chronicles of Placer mining in the Cariboo, and were perhaps, by far, the ones who were fortunate enough to find gold, the most prosperous. The names such as Billy Barker, seem to be the most famous but, the Toop family took more gold than most if not all of the famous names.